El Rancho de las Golondrinas Placita Narrative—Part 1

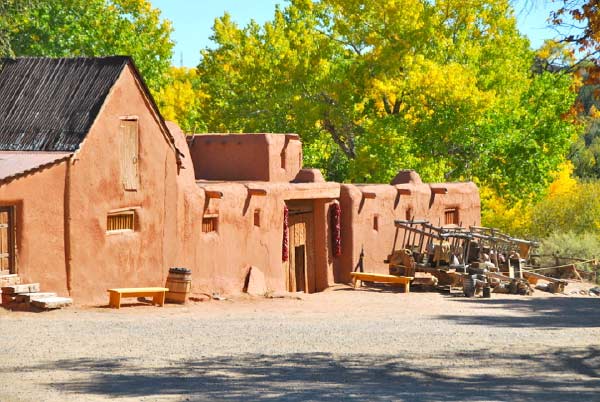

The Golondrinas Placita is a partially reconstructed example of an 18th century Spanish colonial home, built as a defensive structure and positioned on the Camino Real as a Rancho and paraje (stopping place). Built in the 1960s, the entire structure is not original. The Chapel and Founders Room are believed to have been constructed between the 18th and 19th century as a private dwelling and later used as a barn until its transformation into a museum exhibit. Partial adobe foundations were present where the Kitchen and Captives Room are now. Their original form and function is unclear and it is not known with certainty who lived in what is now the Chapel and Founders Room.

Ranchos such as these would have been the residence of one family including any extended family plus servants and slaves. Because of its location on the Camino Real a Rancho and its grounds would also serve as a paraje, accommodating traveling military personnel, government emissaries, Franciscan clergy and traders. In 1780, Governor Juan Bautista de Anza led an expedition seeking to establish a new trade route between Santa Fe and Arispe, Mexico. On November 9th of that year the group marched 4 leagues (approximately 10 miles) south from Santa Fe on their first day and camped in La Ciénega at a place described as Las Golondrinas. While its unknown exactly where Anza camped, one can imagine a large expedition force, full of excitement and trepidation about the adventure ahead, setting up somewhere at Las Golondrinas.

The architecture is specifically designed for defense and is of Spanish origin. Construction is of adobes (sun-dried mud bricks) covered with mud plaster. Roofs are flat and covered with earth. The peaked roof of the Chapel is a later addition from the late 19th or early 20th century when tin roofing material was readily available with the advent of the railroad in New Mexico after 1880.

Entry is through one of the two zaguanes (covered entries) leading to the placita (little plaza) with a noria (well) and hornos (earth ovens) where the family and their servants and slaves would have spent a majority of their time working. A puertón/portón (large door) could be opened for wagons, animals and groups of people, while a puerta de zambullo (small door) was used by individuals. The hornos were in constant use. The horno came to Spain from the Moors in North Africa and to New Spain with no change in design. They were used to bake many foods such as pan (bread), dulces (sweet bread), panocha (sprouted wheat and sugar pudding), cajeta de membrillo which is dried quince and sugar. Hornos were also used to steam fresh corn for chicos ( dried corn) and roast green chile.

The rooms, which surround the placita, make up the defensive exterior walls. The rooms are accessible from one another through interior doors and from the placita through exterior doors. Interior windows looking into the placita are large, allowing air and light into the rooms. Exterior windows are small for defensive purposes and are inset with selenite or mica to allow light in. Selenite is a mineral gypsum whose crystals can occur as tabular sheets which have been used as glass panes as early as the ancient Roman empire. Mica is a sheet silicate mineral that can be used for the same purpose but is typically not as translucent. Exterior windows were also covered with animal skins and wood rejas (bars) while interior windows were barred and/or shuttered. Fireplaces are of adobe and typically constructed in corners.

The roofs are supported by vigas (wood beams), which would have been primarily round and are characteristic of adobe construction. Early examples of finely adzed square beams do exist and are displayed here as well. The ceiling is a mix of round latillas (poles) and rajas (rough strips of wood) laid across the vigas, signifying a lack of milled lumber. Doors are hand hewn with an adze giving them a stout and substantial appearance. It was also common for animal hides to be hung and used as interior doors. While on average, 18th century Europeans and their New World counterparts were slightly shorter than we are today, door height was not dictated by this fact. Rather, the doors are small for a number of other practical reasons. They require less material to make, help to maintain heat in a room when opened and high thresholds on exterior doors help keep rain water, snow, mud and leaves from entering the room. Smaller doors also offer some defense by forcing you to both stoop down and step over the threshold when entering a room or building.

This style of living is directly transplanted from medieval Spain and persisted in other parts of the Spanish colonies. It’s important to remember that the plane of existence in colonial and territorial New Mexico was much lower than it is today in that everyday life in even well-to-do homes occurred much lower to the ground. The Spanish colonials were heavily influenced by medieval and Mozarabic customs. These customs prevailed well into the 19th century as a matter of preference and in some instances as a result of cultural isolation. As a matter of custom and familiarity New Mexicans typically sat, ate and slept on cushions and low stools throughout the 18th and 19th century. This Spanish custom waned in the late 19th and early 20th century because of increasing American influence and affordable mass-produced furniture. Some of these low seating areas or estrados were exceptionally lush with soft mattresses, pillows and textiles. The material culture on display will be a mix of fine and utilitarian Spanish goods, native made material, and Spanish colonial material fabricated on the northern frontier.

Capilla y Sala de Fundadores

Chapel and Founders Room

Sala Grande

Formal Living Room

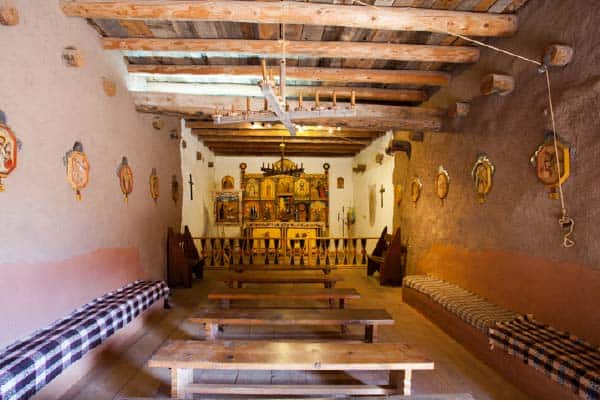

This structure is believed to be the oldest building still standing on original foundations at Las Golondrinas. Originally having a traditional flat roof, the peaked roof of the Chapel is a later addition from the late 19th or early 20th century when tin roofing material was readily available with the advent of the railroad after 1880. The original level of vigas is still visible on the building’s exterior. The wood floor was added when the building was transformed into a museum exhibit. Prior to its transformation into a chapel it was being used as a barn. Based on the layout and objects on display the current interpretation is of a Northern New Mexican Hispanic chapel from the late 19th century. This room does not represent a family chapel or serve as an example of a religious space that would have existed at a Rancho from the 1700s. Rather, this chapel serves as a testament of faith and of the enduring role that religion has played in the lives of New Mexicans from the colonial period to today. In 1994, eleven artists working in traditional styles constructed the altar screen. In 1995, fourteen santeros (saint makers) and a tinsmith made the Stations of the Cross. The Founders Room is where the first meeting of the Colonial New Mexico Historical Foundation was held. This group, under the auspices of the Paloheimos, laid the foundation that brought about the existence of the museum. It now serves as a rotating exhibit space. See “The Bultos of the Golondrinas Chapel” in the interpreter handbook for more information on the altar screen and Stations of the Cross.

As a part of a Spanish colonial home this room would be quite different. It would have served as the Sala Grande (Formal Living Room). This large multipurpose room would have seen a variety of activities but primarily been reserved for the family of the Rancho. Family meals would have been taken here or the family room with service coming from the adjacent kitchen. Members of the family may even have slept in this room. Celebrations and fandangos (Spanish dance parties) would have been staged here and large community and political meetings would also have been held in this room. Distinguished guests would have used this room for lodging.

La Cocina

Kitchen

The Spanish Colonial Kitchen was a hub of activity since it provided the fuel to run the Rancho. Basic meals, mostly served on the run, were probably the norm for most of the people who populated the Rancho. The Rancho owner, his honored guests and his immediate family would be served their meals in the family’s quarters while servants, captives, slaves and workers would eat in the kitchen or grab a quick meal as they went about their business. The food served would be a mixture of Spanish and Pueblo dishes as colonization created a culinary fusion. Vessel forms also reflected this cultural mixture and in many cases traditional Spanish forms such as redware soperos (soup plates) were being commissioned by colonists and made by Pueblo Indians. This utilization of native skill is indicative of the early New Mexican local economy. The preparation and storage of food was a constant and required great effort mostly on the part of women, although men hunted, slaughtered and prepared the meat from game or large domesticated animals. The metates and manos (grinding stones) were used to prepare grains; this arduous work was left to young women both in the Pueblos and on the ranch. Eventually grain mills relieved part of this burden. Tortillas of corn and flour, a modest amount of meat, squash, beans and chile were the mainstays with fruits and other vegetables added in season or stored for use. Spices, salt, and special foods such as chocolate or sugar were carefully stored and protected.

Water at this Rancho was easily accessible but still had to be hauled about and stored for the family’s use and for food preparation. Cooking was done in an open fireplace that had a shelf above for storage of tools and food which could also be used as a bunk, known as a shepherds bed, in especially harsh weather. The hooded hearth or shepherds-style hearth was typical of Northern New Mexico homes and a direct descendent of Spanish hooded fireplaces. The fire was simply made on the floor in the corner with the hood and flu directing smoke out of the room. While split wood such as piñon, juniper and cottonwood were used in fireplaces it was more common to use charcoal. Colonists quickly understood the limitations of resources and wood that had been prepared as charcoal was much more efficient, less wasteful, resulted in kitchens that were less smoky and food that had less ash fall into it. It was so important that Franciscans had native boys assigned to its preparation.

“The cooking is done with charcoal winter and summer; this makes things much easier for the people…The food is better; the cooks are not troubled and filth does not fall into it [food]”

(Dominguez, “The Missions of New Mexico, 1776”, p.311).

In warm weather cooking would be done in the placita. The hornos adjacent to the kitchen were for baking and roasting. Servants and slaves would sleep in the kitchen or other rooms where they worked — like all of the rooms of the Rancho, the kitchen would serve multiple uses. Although the kitchen is full of tools and equipment, it had little furniture. Trasteros (cupboards) which were used to store trastes (dishes) were uncommon in the 18th century but big chests used to store just about everything and used as work surfaces could be found in a large kitchen such as this. The log harinero (grain chest) is an especially prized storage device. Low stools and benches were used for both sitting and for the preparation of food. The practice of eating family style while seated at a table and discussing your day, so much a part of our modern lives, was not a part of life before the late 19th century in various parts of the world. As was typical of the time, meals were a task, not an event and often taken on the go. There was typically an element of segregation so men, women and children often ate separately or in stages. Meals were simply a means of stocking up on calories to get you through the day and were typically treated with little fanfare. The serving pieces such as tin-glazed earthenware (talavera and majolica), silver plates and eating utensils, glassware and pewter were used to serve the Rancho family while servants might have a shared pot of food and a tortilla on a simple unglazed earthenware plate and cup. Everywhere, metal was highly prized so all vessels and other tools made of metal were especially valuable. Pueblo pottery was also widely used for storage and service.

- The harinero (grain chest) is made from a hollowed cottonwood log and shows the ingenuity of Spanish colonists. This form is unique, very difficult to make and not typical of the types of grain chests used in 18th century New Mexico.

- Manos and metates (grinding stones) are on the floor nearby for the daily process of tortilla making.

- In the hearth are iron, copper and ceramic cooking vessels with trivets, iron skewers, spoons, and other cooking implements. Metal items were either brought in by colonists or made by local Spanish blacksmiths. The pottery is a mix of pueblo and Spanish forms.

- Paddles and other implements for the hornos are by the doorway.

- The space above the hearth was multipurpose and would be used to dry food or for general storage. In extreme cold weather it could be used as a sleeping platform/shepherds bed.

- Near the hearth is a low hanging cradle so the women grinding corn or flour on the floor could easily check on the baby. The small built-in banco (bench) is used for sitting and storage.

- The repisa (wood shelf) held the special serving pieces for the family such as majolica, pewter, silver and glass.

- The nicho (niche or recess in wall) with shelves as you enter could hold a variety of culinary objects and household or personal effects including pots of dried food and some of the pots used for food preparation.

- Hanging about the room are baskets, dried food, herbs and tools.

To download a printable version of this copy:

CLICK HERE