El Rancho de las Golondrinas Placita Narrative—Part 2

El Cuarto de Recibo

Reception Room

Located directly adjacent to the large entry zaguán, the Reception Room would have been the realm of the man of the house. The Rancho was far more than a home and served as the center of a business enterprise that included farming, raising livestock, production of wool products including woven textiles, stakes in mining endeavors and the trading of local and imported goods on the Camino Real. There was a need for space to work and for transactions of a wide variety to take place, precious commodities to be sorted and stored, visitors to be received and housed and documents to be prepared and guarded.

Here the Rancho owner, Ranchero, could greet visitors arriving at the paraje from their journey. His honored guests would be offered housing in this room which adjoined the family living quarters — rolled hides and textiles could be spread out for guests or used by the Rancho owner when he wished to have privacy from the rest of his family. Here he might work late into the night going over his accounts or preparing other important documents. From here he might also give his workers their assignments or provide them with their pay in the form of commodities of the realm. Since he might be the only one in the Rancho who was able to read or write, he would have used this space to house precious books or to write upon his escritorio (desk), where he also kept important papers.

Heaped about the room would be special goods that were in transition — either coming from or going to Mexico proper. Since the Rancho produced surplus woolen goods, he was in a position to be involved in the merchant trade by exchanging his surplus for such things as the newly arrived luxury goods or tools — things that could later be sold or bartered to add to the income of the Rancho. In general, this entry room served as the main office, special storage and guest room for the Rancho. The room also buffered the rest of the family from the general comings and goings of non-family members and arriving strangers.

- Animal hides were used as bedding and floor covering as well as door coverings. In addition, woolen mattress-like bags were commonly used as both bedding and seating.

- Writing desks were based upon the Spanish vargueño which was a separate chest sitting upon a table. Smaller boxes with drawers and a hinged front writing surface were often referred to as escritorios and could be transported for use by the literate and well-to-do. Even though ink was constantly in short supply, notaries and scribes played an essential role in the documenting of legal affairs in the colony. Often lacking their services, local alcaldes (mayors) or other educated individuals such as our Ranchero would fulfill this role. Especially important documents were sent back to Mexico City to be entered into the Notarial Archives. Documents such as these, as well as ecclesiastical reports, have provided us with information about life on the far frontier of Northern New Spain. Inventories of goods being transported to and from the colony were kept as much for the government — so that goods could be taxed — as for the merchant.

- As a reception room for the merchant/rancher this room would hold goods either coming or going. The six-board chest was used for transport as well as for storage — it would be raised off the floor. Woven leather chests were made in Mexico proper and in other colonies as well, they were used for both the transport of goods and for storage. A chair for special visitors and for the Rancho owner’s use would represent another example of status and wealth.

- There are piles of woolen goods being set aside in this room in preparation for trade. Other important trade goods for this Rancho might be trained mules, horses and oxen needed for the journey. These might be traded for something rare to the colony such as iron tools or even chocolate, a book, or a bolt of silk.

- The owner’s room might also include the luxury goods used to serve such as pewter, silver, or glass.

- Lighting for his tasks would include precious tallow candles and possibly oil lamps.

- There was little to no hard currency in circulation in New Mexico during this period. This was further complicated by monedas imaginarias (illusory moneys) invented by dishonest merchants to deceive colonists and natives. This consisted of 4 different kinds of pesos to confuse consumers. Silver pesos were valued at 8 reales, de proyecto (inflated pesos) were valued at 6 reales, old pesos were valued at 4 reales and la tierra (common pesos) valued at 2 reales.

However, colonists had a complex system of barter with a clear understanding of how much something was worth, in terms of silver pesos, and what combination of goods in return for something would be considered sufficient payment. Below are a few examples of values from 1776 in the Santa Fe area:

- Fanega (100 pounds or 1.5 bushels) of wheat or maize: 4 pesos

- Fanega of chick peas: 12 pesos

- Fanega of any other legume: 8 pesos

- Cow with calf: 25 pesos

- Cow without calf: 20 pesos

- Wild bull: 15 pesos

- Tame bull trained under yoke: 20 pesos

- Tame ox: 25 pesos

- Yearling calf: 6 pesos

- Other livestock (sheep, ewe, goat): 2 pesos

- Fowl: 4 reales (half of a peso)

- Mule female: 40 pesos

- Mule male: 30 pesos

- Donkey (male and female): 100 pesos or more depending on animal

- Horse (male and female): 100 pesos or more depending on animal

- 1 vara of linen: 2 pesos

- 1 pound of chocolate: 2 pesos

- 1 pound of sugar: 1 peso

- 1 pair of shoes: 2 pesos

- 1 deer skin: 2 pesos

- 1 fat pig: 12 pesos

- 20 eggs: 1 peso

- 1 ristra of chile: 2 pesos in Rio Arriba, 1 peso in Rio Abajo

- 4 fleeces of wool: 2 pesos in Rio Arriba, 1 peso in Rio Abajo

El Cuarto de Familia

Family Room

This room was among the most protected locations in the Rancho since it was entered only by passing through the entry cuarto (room) or by the torreón (tower) room. This was the inner sanctum ruled by the lady of the house where she stored her precious things and raised her children. As such, it is characterized by the use of a variety of textiles for warmth, comfort and decoration and would be the spot where women would gather to work and socialize.

Along the walls are adobe bancos (benches) used for both sleeping and seating, as are the large rolls of bedding that are spread out at night. During the day, these comfortable sofa-like rolls were the spot that women could use for seating and lounging as they worked. Some of these low seating areas or estrados were exceptionally lush with soft mattresses, pillows and textiles. Like the entry room, a small fireplace provided heat and could be used for some modest cooking although most of the serious food preparation took place in the kitchen. Servants would serve the family its meals in this room as they sat upon their rolls of bedding or upon low stools.

The chests so ubiquitous to the entire Rancho were not only for storage but could also be used for serving and as work surfaces. Little other furniture graced the room although a chair or two might be reserved for special guests. An altar area in the room was maintained for the family’s private worship. Above a modest table were stacked religious images that mimic the form of the more elaborate altars and altarpieces to be found in the churches in town. Some large Ranchos had their own small chapels that could serve the family and neighboring colonists. Small windows with a form of glazing made of selenite or mica allowed some light to enter while larger windows with shutters faced the interior courtyard.

- Hanging blankets and examples of New Mexican weaving, which would be brought down at night for warmth and hung during the day for safekeeping.

- Woolen mattress, made from jerga (utilitarian weaving) and stuffed with wool fleece are throughout the room and used for sleeping and sitting.

- Altar area with retablos (painting on wood of a religious figure), bultos (wood statue of religious figure) and other personal religious paraphernalia being used as a private devotional area which has a fine colcha embroidered altar cloth covering the table (colcha means bed covering but in this case colcha refers to New Mexican embroidery, which utilizes a couching stitch called the colcha stitch). Retablos are stacked and placed in a manner that reflects the arrangements of larger altar screens. Saints depicted would have been from the pantheon of Franciscan saints as well as those that might be personal to the family. Colonial New Mexico did not have an official Patron Saint but a few of the many religious figures commonly prayed to by Spanish colonists were San Francisco de Asis (Saint Francis of Assisi), San Pablo (Saint Paul), San Isidro (Saint Isidore), Santo Niño de Atocha (Holy Child of Atocha) and various avocations of the Blessed Virgin including Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe) and Nuestra Señora del Santísimo Rosario (Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary).

- Women’s fine clothing, such as rebozos (shawls), would be stored in chests.

- In front of the fireplace women would gather to do their work — a malacate (spindle) and embroidery in process can be seen.

- A small table is being used in the general hearth area and the family would have had a number of woolen mattresses being used as seating by the ladies of the house.

- Clay candle holders with tallow candles provide light for the work being done.

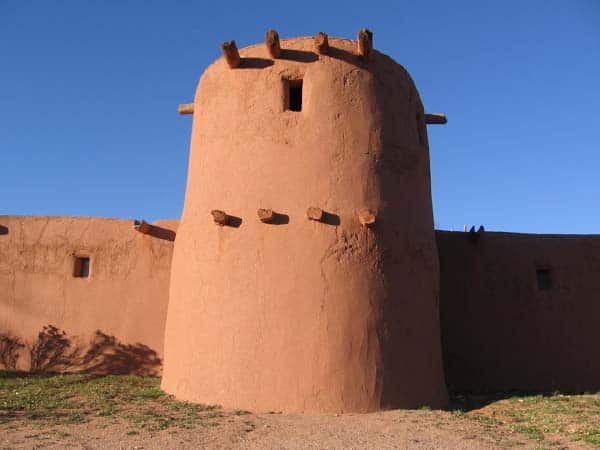

Torreón y Zaguán al Torreón

Tower and Tower Entrance Room

Torreones were a common sight throughout Northern New Mexico during the Spanish Colonial period. Colonists were responsible for defending themselves, as the soldiers of the presidio (fort) could not be notified in time to protect their fellow citizens. These towers provided a place for the Spanish to retreat while under attack.

These multipurpose structures were also used for storing food, water, tack and weapons used in the defense of the Rancho. This particular torreón is built into the Rancho complex but many were also constructed as stand-alone towers in a strategically defensible position offering expansive views. On the upper level, a sentinel stood watch and was ready to warn others of approaching danger by any means available including blowing a horn, beating a drum, shouting or ringing a bell. Field workers would run to the protection of the walled placita while others would enter the Torreón to fight off the enemy. Raiding was typically done by both the Spanish and native tribes in order to obtain needed supplies, animals and captives but not as a matter of absolute extermination. Attacks were usually over as quickly as they started and may have resulted in injury, death or captivity.

One such attack is documented as taking place in La Ciénega in the writings of Franciscan priest, Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez. On Thursday June 20th 1776, a party of Comanche warriors attacked ranchos in La Ciénega killing nine men and boys and taking two young children captive. Antonio Sandovál, the owner of El Rancho de las Golondrinas, lost his 19 year old son Jose Sandovál and nephew Santiago Mascareñas, who were killed as they tended crops. Scenes such as this were typical on the northern frontier as uneasy relations resulted in tragedies on both sides.

- Weapons stored in the torreón included escopetas (Spanish muskets), lances, swords and bows. Colonists would use whatever they had at their disposal to defend themselves. Gunpowder was constantly in short supply from Mexico and the Spanish often used bows, arrows and lances. Barrels contained what little gunpowder the Rancho possessed.

- Horse tack was stored here as well. Saddles, bridles and blankets hang on the walls. Straps, rope, and cinches were often made from horsehair, which produced superior reins as well.

- An aparejo is stored here. Aparejos are pack pad saddles that go over the backs of donkeys and mules to form the base of the packing system and protect the animal from injury. Large atajos (caravans) of pack mules and donkeys would travel the Camino Real carrying goods and in the 19th century would travel west to California and north as far as Wyoming. Arrieros (muleteers) were responsible for packing and taking care of the animals. This entire system of packing was passed on to the Spanish from the Moors of North Africa and was a guild-controlled profession in Spain.

La Despensa/Dispensa

Pantry

Infrequent wagon trains from Mexico, drought and raids made it imperative to take rigorous measures to store and stock provisions. Starvation was a very real possibility and times of famine would stalk the fledgling colony. Wild game was an indispensable source of protein. Large flocks of sheep were important for survival and f or revenue. Corn, beans and squash provided the most important foodstuffs and these were stored in great abundance by the colonist and guarded in the Despensa (pantry) from both pests and humans alike. Preservation of food was limited to salting, smoking and drying — canning was to come much later. Seed storage was another significant use for the Despensa. Colonists in New Mexico would look to their Pueblo neighbors when they had failed to adequately harvest sufficient quantities of food. These supplies were either acquired through the encomienda system (mandatory tribute and labor) or taken by outright force, which often resulted in starvation for the Pueblos.

- Dried food such as chile and corn are stored here. They are both hanging as ristras and piled into sacks.

- Containers of seeds are stored here and used for planting in the spring. Seed saving was an important aspect of Spanish Colonial agriculture. The finest specimens of vegetables would have been selected, dried and the seeds removed.

- This room also serves as the storage space for agricultural implements of the field such as rakes, digging sticks, hoes, and sifters for grain.

- Measuring containers for grains: fanega, almud and cuartilla. A fanega constituted the standard Spanish volumetric unit for dry measurement. A fanega of dry corn was equivalent to approximately 100 pounds of grain or 1.5 bushels. An almud is one-quarter of a fanega. The cuartilla is 1/12th of an almud and 1/48th of a fanega.

- Barrels are in this room for food storage such as dried grains and salted meat. The baskets would have been used for gathering fruits and harvesting vegetables.

- Dried fruits and vegetables could include apricots, peaches, apples raisins, peas, beans, onions and garlic, also melon and squash—such as watermelon, and pumpkin.

- Fresh vegetables include tomatoes, cabbage, onion, lettuce, radishes.

- Dried grains—corn and wheat are stored in the harineros (grain chests or bins).

- Glass and pottery vessels are for the storage of oils, wine, brandy, vinegar, and tallow.

- Luxury goods and foodstuffs such as olives, chocolate, sugar and tobacco would be stored here for safe keeping.

- Dried and curing meats such as venison, sheep and buffalo would hang from the vigas.

- Dried herbs hang from poles and materials for food preservation such as salt are kept dry here.

To download a printable version of this copy:

CLICK HERE